LEGENDS OF

LIGHT MUSIC

Leon Young

"PASSING

NOTES"

A Brief Biography of

LEON EDWARD STEPHEN YOUNG

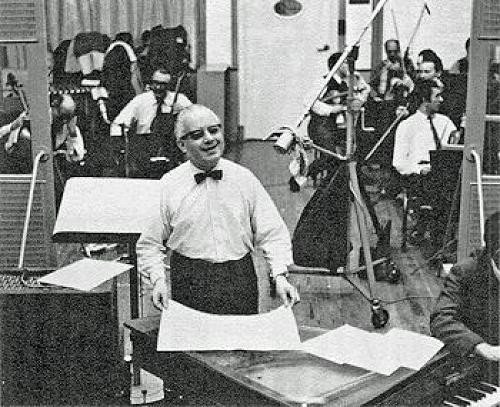

Arranger & Conductor

(1916-1991)

by his son MALCOLM HARVEY YOUNG

Leon Young was born on 21 April

1916, the son of Leon and Ethel

Young. Named Leon after his

father, he is especially

treasured, particularly as his

younger brother, Raymond, was

soon to die in infancy.

Leon senior was a signalman on

the railways, and a few years

after his son’s birth he was

transferred to the signalbox at

Strood near Rochester. Leon

senior was a devout Salvationist,

and his family were soon embraced

into the local Salvation Army

corps, with father playing cornet

in the band and young Leon

becoming the little side-drummer

boy. His musical education had

begun and before long, he had

graduated to cornet and later to

trombone.

His schooling took place at

Rochester Mathematical School

where he was destined to pursue

studies in electrical

engineering. But one, May Baker,

presciently noting his natural

musical talent, referred him to

Percy Whitlock, the assistant

organist at the cathedral. Percy

had himself been a musical

prodigy as a cathedral choirboy

from the age of seven and by 1930

had established a fine, if local,

reputation for his musicianship.

In his appointment diary, he

notes of his new pupil - 'Leon

Young - Pfte - a protegee [sic]

of May Baker at Technical School.

Salvation Army Parents - v strict

- she wants him to gather all

possible musical experience'.

Accordingly, at 2.15pm on 23

January 1930, a surely nervous

thirteen-year-old Leon climbed

the steps of No. 9 King Edward

Road, Rochester, tentatively rang

the bell beside the double

fronted door and presented

himself for his first piano

lesson with Percy Whitlock. An

infinitely kindly man and, like

many an organist and, unbeknown

to Leon, a keen loco-spotter and

railway-modeller, those few

months and the time spent in the

cathedral organ loft were to be a

life-long inspiration.

At the time, it was assumed by

everyone that PW would naturally

succeed the illustrious Hylton

Stewart as the cathedral

organist, but when he was passed

over in favour of a certain

Harold Aubie Benntet he moved to

Bournemouth. Pastures new and

much wider recognition, not only

as a church organist and concert

organist with the Bournemouth

Municipal Orchestra but also as a

composer of light (and not so

light) orchestral works very much

in the English tradition - a

curious blend of the sacred and

the secular which was also to

characterise the musical life of

his pupil.

Percy died of a stroke in 1946

but his music lives on. Had he

lived, how much he would have

enjoyed following the career of

our subject, his onetime pupil.

In 1935 the Southern Railway

completely remodelled the station

at Tonbridge and a brand new,

state-of-the-art West signal box

was built. Once again Leon senior

was transferred to become its

first signalman and once again

the Young family found themselves

in a new town. His schooling now

behind him, nineteen year old

Leon found himself a job as a

grocer's assistant, dispensing

ill-informed advice on seed

potatoes to men with three times

his years and experience. His

father was soon to become Station

Foreman on the railway and

Bandmaster at the SA Citadel.

Perhaps to over-compensate for

perceived favouritism, young Leon

found himself becoming the band's

whipping-boy. All the mistakes

were his! But a new town brings

new opportunities. The Baptist

Church in the High Street was

seeking an organist and the Co-op

Choir (a large body in those

days) was seeking a conductor.

Leon applied for and was

appointed to both posts. And then

there were the local semi-pro

dance bands. Leon soon swapped

his SA uniform for some

co-respondent shoes and a place

behind an art-deco music stand.

Alfred Harvey, one of the deacons

at the Baptist Church who had

appointed Leon to the organ stool

was also the Sunday School

Superintendent. He and his wife

Alice had a daughter Grace who

not only sang in the front row of

the church choir but also sang in

the front row of the Co-op choir.

She also belonged to the Womens'

League of Health and Beauty. In

November 1939 they were married

at the Baptist Church and set up

home with the bride's parents in

Hectorage Road. The wedding was

not without incident as the

bridal cars had delivered the

bridesmaid and principal guests

but forgotten to return for the

bride and her father! The

organist repeated his extremely

limited repertoire over and over

again. Leon must have thought

that he had been stood up. The

matter was happily resolved and

such was the throng outside when

they finally emerged that the

regular bus service was delayed

until the High Street could be

cleared.

But Hitler had other ideas. We

were at war. In the new year, the

Royal Marines were seeking

'Musicians for service at sea in

HM Ships'. What better way to

serve King & Country than

with your trombone! Leon duly

presented himself as an HO

(Hostilities Only) at the Royal

Naval School of Music at Deal in

the expectation that the war

would be over by Christmas. But

then came Dunkirk and the story

of the little ships. So it was

off to Plymouth for marching

drill and gunnery practice.

The military mind associates

music with gunnery. Perhaps the

mathematics involved is common to

both, or perhaps anyone

intelligent enough to read

musical notation will be equally

capable of calculating the

trajectory of shells. For either

reason, RM bandsmen are consigned

to the Gunnery Transmitting

Stations in the bowels of HM

ships at sea.

After a brief return to old

haunts at barracks in Rochester

and Chatham, it was now off to

Glasgow to embark on the newly

built and commissioned Light

Cruiser HMS Hermione. She was

immediately to see service in the

Denmark Straits in pursuit of the

German battleship Bismarck which

was seen in a snowstorm on 30 May

1941 and subsequently sunk that

very night.

Then back to Scapa Flow the next

month and thence to Gibraltar to

join X-Force and later the famous

Force H in the Mediterranean,

escorting convoys of aeroplanes

to Malta. There had been little

opportunity for music so far but

that was to change. Leon had

become firm pals with a fellow

bandsman, Max Nicholls, from

their first days at Deal and

together with a few like-minded

bandsmen they formed a small

dance band which performed in

Gibralta's clubs, officers'

wardrooms ashore and over the

local radio as well as aboard

other ships and in impromptu jam

sessions with other groups (even

borrowing instruments) whenever

the opportunity occurred. The RM

band also played at official

events ashore in Gibralta and

Leon had the opportunity to play

the organ at the cathedral and

the Presbyterian Church and, at

the other end of the

Mediterranean, on occasion at

Valetta cathedral on Malta.

Days and nights at sea were

unendingly eventful - bringing

down raiding aircraft, ramming

and cutting in half the Italian

submarine Tembien on the surface,

rescuing downed airmen, shelling

enemy ships and shore batteries

and generally protecting the

aircraft carriers, enabling them

to safely deliver over 200

aircraft to Malta.

One day in 1941 Leon received

news aboard Hermione that back

home in an upper room at Hope

Villas his wife, Grace, had given

birth in the early hours of

Saturday 13 September to a baby

son. Leon rushed to tell the

captain. As an officer and a

gentleman, Captain Oliver greeted

the glad tidings with all the

great joy appropriate to the

occasion but he must have had

more pressing considerations on

his mind, not least the prowling

U-boats! One such U-Boat (U205)

found her target on the starlit

but moonless night of 16 June

1942 and sent Hermione to the

bottom of the Mediterranean, some

ninety miles from Tobruk,

'rearing up', as described in The

Daily Mail, 'like a huge whale'.

U205 was subsequently commended

by Rommell for sinking Hermione,

in his own words, 'the terror of

the Mediterranean'.

After 45 minutes of paddling and

gulping the dark, oily water,

Leon and Max were rescued by the

destroyer Beaufort and taken (ice

cold?) to hospital in Alexandria.

A week later they secretly

discharged themselves and

literally leapt aboard the HMS

Queen Elizabeth (not the liner,

the battle ship) which had been

in dry dock but was now departing

for Cape Town, South Africa via

the Suez Canal. Hermione had been

to Cape Town earlier that year as

part of a British Force to

capture the Vichy-French island

of Madagascar to prevent it

falling into the hands of the

Japanese. This was a splendidly

successful Hornblower-style

operation undertaken before

returning to the all too familiar

waters of the Mediterranean.

On crossing the Equator on the

way down, Leon had been subjected

to the 'crossing the line'

ceremony for novices. No such

novice this time though. Now it

was crossing the line southwards,

east of Africa, rounding the Horn

and then sailing northwards up

the Atlantic, crossing the line

again this time west of Africa

and after two months and several

ports of call, they arrived at

Chesapeake Bay and then

Portsmouth, Virginia, USA.

A happy and musical couple of

months was to follow. Still

billeted aboard the battleship

Queen Elizabeth and later at the

US Marine Corps barracks, Leon

and friends formed themselves

into 'The Hermione Three' and

played at clubs and dances to

great acclaim. They presented a

glamorous image and, invited

daily into the homes and churches

of local families, they were

feted as 'England's Proud Sons'.

But it was over all too soon and

before long it was an overnight

train via New York to Halifax,

Nova Scotia where they boarded

the Queen Elizabeth (this time

the liner) bound for Greenock and

ultimately the RN School of Music

at Scarborough. Much of Leon's

time here was spent arranging the

music and putting together the

musical extravaganza Tokyo

Express. This was one of two

official Naval Shows of the war

(the other was Pacific Showboat)

and it opened at the Lyric

Theatre, Hammersmith in June

1945.

Michael Mills was the producer

and Norman Whitehead was the

musical director. Band Corporal

L.E.S.Young also performed in

item 17, 'Six Hands in Harmony'.

Another pianist in the show was

Signaller Trevor Stanford who

after the war changed his name to

Russ Conway. Although originally

destined for HMS Agamemnon, the

show finally toured Canada

instead, but without Leon.

Max was part of the RM band's

rhythm section which, with five

brass and five saxes, 'lifted the

roof off'. Leon was a grocer's

assistant when he left civvy

street in 1940 but by the time

the war had ended five years

later, he was a fully-fledged

orchestral arranger and all-round

musician.

Despite his mother-in-law's

protests (get a 'proper' job), he

resolved to make music his

full-time career and after

trudging the streets of London in

his demob suit and trilby, he

soon secured a position as staff

arranger at Francis, Day &

Hunter, the publishers, in

Charing Cross Road.

Maybe as a result of contacts he

made on Tokyo Express or through

his new associates, within two

years he was contributing

arrangements for Tommy Handley's

ITMA, then the most popular and

prestigious show on radio. Each

programme contained a musical

spot featuring the BBC Variety

Orchestra conducted by Rae

Jenkins. Among the arrangements

contributed by Leon Young in 1947

and 1948 were Auld Lang Syne,

Crazy People, Gale Warning

(conducted by Guy Daniels with an

augmented orchestra), Knees Up

Mother Brown, My Boy Willie,

Three Negro Spirituals,

Whit-Monday Medley and Under the

Spreading Chestnut Tree -

collectors' items all.

'Underneath the Spreading

Chestnut Tree' was chosen for the

Royal Command Performance

attended by King George VI, Queen

Elizabeth and Princess Margaret

in the Autumn of 1948 because the

song was a favourite of the

King's from his Duke of York's

Camps for boys. It is interesting

to note that Leon wove into the

closing bars of his arrangement

the tune of 'Here's a Health unto

His Majesty' but it's not known

whether the royal party noticed.

The FDH shop enjoyed a double

frontage at the top of Charing

Cross Road on the East side, the

windows of which displayed a

gleaming array of musical

instruments and sheet music.

Customers and artists alike would

use this entrance. But at the

side of the building, on Denmark

Street, was an anonymous faded

doorway for the use of lesser

mortals, behind which three

flights of stone stairway with

iron handrail led to a top floor

landing, home to an ancient gas

stove and a butler sink.

From there a dim, windowless

passageway led to the offices of

the arrangers and copyists

overlooking Charing Cross Road.

Halfway along the passage on the

left was Leon's office, a small

room, perhaps eight or nine feet

square, which looked out over

Denmark Street. It was sparsely

furnished with a desk and chair,

an elderly leather visitor's

chair and an upright piano of

doubtful parentage. It had all

the ambience of an Edward Hopper

scene. The aforementioned

facilities on the tiny landing

afforded these professional

musicians complete autonomy. They

could brew their own tea and

coffee by setting the hob burners

to p, mp, mf, f and even ff

according to the intensity of

heat required. Occasionally they

were summoned to the sumptuous

offices on the floor below, there

to meet a visiting artist in need

of a special arrangement.

Among the fledgling artists whose

careers Leon helped to launch in

this way were the schoolgirl,

Petula Clark, and the young Max

Bygraves.

Although still living with his

in-laws, Leon now felt

sufficiently well established in

a secure and rewarding job to buy

an Austin 10 and, ever an

animal-lover, a long-haired

marmalade cat called Marmaduke.

One day in 1948, a member of his

church choir whispered that the

house next door to hers in

Douglas Road, would shortly come

onto the market. At that time

such insider information enabled

Leon to secure the property

forthwith. From this modest

semi-detached, within walking

distance of the station, Leon

commuted the thirty or so miles

to and from Charing Cross daily

until he retired from FDH.

One of the first items to be

installed in the new home was a

Bechstein baby grand piano. But

it was insufficiently 'baby' and

the front bay windows had to be

removed to get it in, an exercise

which resulted in a crack in the

frame (shades of Laurel &

Hardy). This was not apparent

until the instrument came to be

sold in later years.

Before the war, Tonbridge was

home to a Society of Local

Amateur Musical Players (LAMPS),

dedicated to producing a show

each year. Together with

like-minded friends, the LAMPS

was reformed in 1948 with Leon as

its Hon. Musical Director. Their

first show in 1949 was No, No,

Nanette performed at the old

Repertory Theatre in Avebury

Avenue, an edifice adequate at

front of house but devoid of

dressing rooms backstage save for

some draughty lean-to sheds which

denied modesty to the female cast

members, even from the road

outside. Rehearsals were held at

Phil's Cafe attached to the

boathouse on the river. A

single-storey wooden structure,

it sported a large meeting room

ideal for the purpose.

Postwar austerity lingered on in

Britain into the 1950's but the

deprivations of rationing had

been somewhat alleviated in the

Young family at least by the

regular arrival of parcels of

food and clothing from the

affluent friends in America whom

Leon had met in Virginia during

the war. In 1951 they came over

for a reunion with 'England's

Proud Sons' and to see the

sights. The same year saw the

advent of the New Elizabethan era

heralded by the optimism of the

Festival of Britain.

As the decade progressed,

increasing prosperity (not least

for the local Ford dealer)

permitted a certain

self-indulgence. The Ford Prefect

became a Consul which became a

Zephyr which became a Zodiac.

In 1953 the Decca record label

issued two 78s containing two of

Leon's most famous and memorable

arrangements, Charlie Chaplin's

theme from Limelight and Ebb

Tide. The label had recently

signed up Frank Chacksfield to

add to their roster of Stanley

Black, Mantovani and Robert

Farnon. This was to be a 40-piece

orchestra with a large string

section and Leon was approached

to provide the arrangements. He

made fine use of such resources

and, in the event, conducted the

recording sessions as well. Both

titles won Golden Discs for sales

in America, the latter being the

first-ever British non-vocal to

reach number one in the American

charts.

Leon composed the memorable

soaring counter-melody for solo

violin which is now synonymous

with Limelight while taking a

bracing walk on the promenade at

Burnham-on-Sea. The success of

this recording led Charlie

Chaplin to invite Leon to

Switzerland to work with him on

future projects, an invitation

which he declined.

There was also a brief foray into

film music with a score for a

B-feature war film produced by

the Danziger Brothers. The

Danzigers were better known for

their entrepreneurial abilities

than for their artistry and the

title is now mercifully obscured

by time. However it occasioned

the purchase of an intricate

stopwatch so that Leon could

accurately match the music to the

pictures as they were screened on

the wall of the recording studio.

This all came to nought on the

cutting-room floor and Leon's

career in cinema progressed no

further.

More and more Chacksfield

long-playing discs were released

by Decca. Conceived as 'concept

albums', they were characteristic

of their time and are a showcase

of Leon Young's arrangements. He

is credited with some of them in

the sleeve notes but only

industry-insiders knew the truth

- that he arranged almost all of

them and conducted most of the

sessions as well. Frank

Chacksfield was himself an

arranger but of limited talent

and it suited him well to

maintain the popular belief that

the work was all his own.

Many an arranger, Nelson Riddle

included, has had their work

misappropriated by another. Now

in his mid-thirties, Leon had the

enthusiasm, the energy and the

stamina to sustain the gruelling

demands of his round-the-clock

career. Many were the all-night

writing sessions at home and at

weekends, Jock Todd, his copyist,

would come down and stay

overnight copying out the parts

for the next session. Jock was a

professional copyist and semi-pro

accordian player with an

entertaining turn of phrase. He

christened these weekends the

Crotchet Factory.

Copyists work in ink with a

special splayed pen-knib which,

flourished expertly, will produce

crotchets, quavers etc at a

stroke. The downside is that the

ink took a while to dry so his

parts were regularly spread out

all over the music room floor.

'Get that sad cat out of here',

Jock would cry whenever Marmaduke

ventured to add smudged inky

paw-prints to the music. Leon's

full-score, on the other hand,

was written entirely with a soft

pencil which permitted of much

rubbing out before perfection was

achieved.

The tools of the arranger's trade

were modest - a pencil, a

pen-knife sharpener, a rubber, a

ruler (for drawing full-length

bar lines), some pre-printed

manuscript paper and a board to

provide a hard surface.

Throughout his life, Leon's

chosen ruler was a promotional

gift from Confederation Life,

wooden with a metal edge, and his

chosen board was the back of a

broken art deco mirror with

bevelled corners that had

belonged to his mother-in-law.

The sound was of a constant

tap-tapping in the making of

small-headed crotchets with

detached tails interspersed with

the urgent wiping away of rubber

shards with the side of the hand.

The work was composed entirely

within his head with only

occasional visits to the piano

just to try out alternative chord

sequences.

Both Leon and Jock were sustained

throughout these marathons by

large cups of black coffee and a

constant supply of Players Gold

Leaf cigarettes bought from the

local newsagent by an under-age

junior member of the family. That

same person was also despatched

with equal regularity to the

railway station with parcels of

parts destined for the BBC

broadcasting theatres or the

recording studios. So familiar

was the sight of a small boy and

a large parcel on the platform,

that registration formalities for

Red Star were dispensed with and

the parcels placed directly into

the hands of the guard who could

be trusted to safely deliver them

for collection at Charing Cross.

Jock Todd bought the Zodiac

second-hand, by this time

bristling with extras - wing

mirrors, a sun-visor and a

chromium-plated exhaust

deflector. It was a bit flash.

Other copyists associated with

the crotchet factory at that time

were Albert (Bert) Elms and Edwin

(Ted) Astley, both of whom went

on to greater fame as the

composers of many a TV theme

tune.

Although a hugely successful

songwriter and tunesmith, it is

well-known that Lionel Bart could

neither read nor write a jot of

music so Leon was invited along

to note down the melody lines for

Oliver as Lionel sang them to

him. But it seems that the

experience disinclined him to

make the arrangements as well.

They were subsequently undertaken

by Eric Rogers.

By 1958 television was

well-established in the homes of

Britain and this year saw the

first screening of The Black and

White Minstrel Show featuring the

George Mitchell Singers. Leon had

known George since the 'George

Mitchell Showtimers', as they

were called after the war, had

recorded a memorable LY

arrangement of Ten Green Bottles.

They subsequently enjoyed a long

and cordial working relationship

based on mutual respect, Leon

regularly contributing

arrangements for the Minstrels

which would exploit the

particular talents of each of the

star soloists as well as the

ensemble. The programme was a

huge favourite with the public

but by 1980 it was considered to

be offensive to black people and

so was discontinued.

Perhaps because of the pressure

of all this commercial work, Leon

began to feel the need not just

for recognition within the music

industry but for academic

recognition as well. This led him

to find the time to study for the

Associateship of The Royal

College of Organists (ARCO),

whose exams are acknowledged to

be among the most demanding in

musical academia, both practical

and written. Of course, the

theory and the practical were no

problem at all but poring over

weighty tomes on the history of

English Church Music proved more

challenging. However, he passed

with flying colours and promptly

went on without a break to take

and pass the Fellowship (FRCO)

exam as well. As if that was not

enough, he also took private

one-to-one lessons in classical

conducting which might have

seemed superfluous at this stage

in his career.

At this time he was also busy

composing, arranging and

conducting numerous titles for

the Mood Music library and at

home there were two services a

Sunday at the Baptist Church and

choir practice on Thursdays

preparing an anthem. But all this

took its toll and he was laid up

with a back problem, confined to

bed on a hard board for several

weeks. He had a television

perched atop the wardrobe to keep

in touch with his television

broadcasts and a radio to hear

his broadcasts with various BBC

orchestras, not to mention

programmes on topics which would

otherwise have been of no

interest at all - 'Gardeners'

Question Time' is all new to one

unable to distinguish a daffodil

from a tulip.

There was no escape. Not to waste

the time, Leon spent hours

writing out various combinations

of instruments, 'wish lists' on

small sheets of paper, in pursuit

of an original sound as

distinctive as that of Mantovani

or Bert Kaempfert. Such an overt

style eluded him but his

'signature' is readily apparent

in the distinctive string voicing

(noted by many), the use of

woodwind (two flutes a

favourite), a marked fondness for

the flugel-horn and certain harp

colorations. His favoured lady

harpist smoked a pipe throughout

the recording sessions.

Enter the Swinging Sixties and

the emergence of youth culture -

Carnaby Street, psychedelia,

Elvis, Rock & Roll, The

Beatles, and above all the

dominance of the electric guitar

and of small groups. How much

cheaper were four lads than a big

band or a large orchestra.

You might think that this would

prove to be the death knell for

Leon's style of music but,

largely thanks to Denis Preston,

this was not to be. Denis was a

record producer whose particular

talent lay in bringing together

sometimes unlikely pairings of

artists at his Lansdowne Studios.

He suggested the formation of an

orchestra consisting of the very

top session musicians of the day,

brought together solely for

recording purposes and to be

called 'The Leon Young String

Chorale'.

Leon resisted the word 'chorale'

at first, perhaps because it

offended his classical

sensibilities, but he was

persuaded that it would be a good

marketing device as 'chorale' was

a fashionable word at the time.

Other artists recording at

Lansdowne were Elaine Delmar,

Bent Fabrik and Roger Whittaker,

all of whom benefited from the

accompaniment of The LY String

Chorale with his distinctive

arrangements. Perhaps the most

memorable of these is the

characteristic LY arrangement of

Roger Whittaker's Durham Town.

There were also discs issued on

various labels featuring the

String Chorale alone, the finest

of which being Ellington for

Strings, a selection of the

Duke's compositions specially

arranged by Leon for the album

which received enthusiastic

approval from the man himself.

But, of course, the most famous

association of this period was

with Acker Bilk, an unlikely

pairing indeed. Everyone who

remembers the sixties remembers

Stranger on the Shore. Issued as

a single on 25 November 1961 it

went straight to number one and

stayed in the charts for

fifty-eight weeks. Acker's tune,

originally entitled 'Jenny' after

Bernard's daughter ('Acker' is a

west-country pseudonym for

'mate') was given to Leon as a

single line on a scrap of paper.

From this he produced an

arrangement of exemplary

craftsmanship and characterised

by the restraint so typical of

his mature style. The change from

minor to major ('How strange the

change...') at the close is so

very LY.

The success of this track in the

UK was mirrored in the US,

resulting in Acker & Leon

being invited to appear on the Ed

Sullivan show in New York. The

indignity of Leon's strip-search

by US customs officials was in

sharp contrast to the subsequent

luxury he enjoyed at the

Algonquin Hotel. He also had to

contest litigation with Acker for

recognition of his contribution

to the best-seller. It was

ultimately settled 'out of

court'.

Adrian Kerridge was 'the engineer

with an ear' and Peter 'Letraset'

Leslie designed the record

sleeves. The contribution of the

engineer cannot be readily

dismissed. Over and over again we

hear of the interpretation of

such-and-such a conductor but the

engineer can control the overall

balance and bring out the

pertinent instrumental emphasis

far more than can the conductor.

The 'interpretation' lies within

his hands.

At home, Leon, now habitually

described in the local press as

'that well-known local figure, Mr

Young of the BBC', had been LAMPS

Musical Director on fourteen

shows from No, No, Nanette in

1949 to Katinka in 1962. In the

intervening years the Repertory

Theatre had changed its name to

The Playhouse and was finally

demolished in 1955 to make way

for Sainsburys. The society then

moved to The Royal Victoria Hall

at Southborough on the outskirts

of Tunbridge Wells and opened in

1956 with Mr Cinders. Leon became

President of the LAMPS in 1963.

The old sticker & tracker

organ at the Baptist Church in

Tonbridge High Street had been

built by Lewis & Co in 1894

at a cost of £236.15d and was

now showing its age. Leon drew up

the specification for a rebuild

to be undertaken by Hill, Norman

& Beard. An organ fund was

launched in 1961 which raised

£5,500. The new organ with a

detached console and casework by

Herbert Norman was consecrated

with an inaugural recital on

Saturday, 4 December 1965.

Leon's programme included works

by J.S.Bach, Louis Vierne, Paul

Hindemith, Jean Langlais, Flor

Peeters and Franz Liszt among

others. Three years later the

River Medway burst its banks and

a devastating flood of swirling

muddy water rushed through the

church. The organ was dismantled

to be dried out and when the

church was demolished and

relocated from the High Street to

the north end of town in 1973,

the organ was rebuilt to the same

specification but in different

casework on the new site. But, by

this time, Leon was organist at

the Parish Church, a change of

denomination and repertoire.

During the 1970s and 1980s BBC

radio broadcasts continued with

various BBC orchestras hosted by

presenters such as Alan Dell,

John Dunn, James Alexander

Gordon, Jimmy Kingsbury, Sarah

Kennedy, et al. Leon diligently

recorded these broadcasts on

78rpm 'acetates', open reel tapes

and latterly stereo cassettes in

recognotion of their undoubted

worth and for private study. Much

of the archive survives, as do

most of the original MSS and

parts. Arranging continued too,

both staff and freelance, but

there was less recording and more

time for original composition.

Among some unusual compositions

can be found a novelty brass band

piece for euphonium and a violin

capriccio, both as yet

unperformed. Leon employed a

number of pseudonyms for his

original compositions including

Gil Adam, Gil Adams and Malcolm

Harvey. A much earlier

composition performed regularly

at services of remembrance is a

fanfare, To Comrades Fallen,

commissioned for the state

trumpeters of the Royal Marines.

There also followed a long

association with Sidney Thompson

and his Time for Old Time

programme which also resulted in

a series of LPs. This might seem

an unlikely association as Leon

had never set foot on a

dance-floor in his life and would

have had two left feet. But the

knowledge and craftsmanship that

he brought to the arrangements

was much appreciated.

His deepening commitment to

church music led him to install a

classically-voiced organ with

full pedal board alongside the

Bechstein. This enabled him to

practice at home without turning

out on cold, wet winter nights to

practice in a draughty church.

But when Songs of Praise was

broadcast from Tonbridge Parish

Church, Leon could be glimpsed at

the console, not attired in FRCO

hood and gown, but in his

shirtsleeves. To him, this was

just another professional

recording session.

In October 1983 he was pleased to

attend the founding of the Percy

Whitlock Trust at the old RCO

building (of fond memory with its

Italianate friezes) alongside the

Albert Hall. Malcolm Riley (PW

Trust secretary and founder

member) recalls that LY was just

as modestly retiring that day as

he was as a teenager at PW's door

in 1930.

His in-house arranging at FDH had

become increasingly demoralising.

This was the time of Adam Ant and

of the Sex Pistols. While the

other arrangers tried to make

reasonable piano copies, Leon was

required to make orchestral

arrangements of 'Matchstalk Men

& Matchstalk Cats & Dogs'

or 'Grandma, We love You'.

His disenchantment was complete.

With his ironic daily mantra, 'I

hate music', he was just serving

out his time until retirement in

1981. But his commitment to his

fellow musicians remained

constant and, as a long-time

member of The Performing Right

Society, he joined the panel of

the Members Fund and would make

occasional house-calls to assess

personal need.

With the daily commute to Charing

Cross now a thing of the past,

proximity to the station was no

longer necessary and in 1985 Leon

& Grace moved to a bungalow

at the north end of the town. The

organ moved too, but not the

Bechstein as Leon now had the

compact Challen upright brought

with him from FDH. He also moved

to the organ stool at Frant

church on the further outskirts

of Tunbridge Wells, perversely in

quite the opposite direction.

The music of the Salvation Army

and the brass band movement in

general drew him back. His

interest in brass bands had

sustained him throughout his life

and he had served as an

adjudicator at occasional

contests in the south of England.

In November 1989, Leon &

Grace celebrated their golden

wedding anniversary with a dinner

attended by family and close

friends, many of whom had been

there fifty years before, but

none from the music industry.

We have seen how the railway and

the Salvation Army exerted such

influence upon his early life

and, fittingly, so they did at

the end. On a cold Saturday

evening in January 1991, Leon

& Grace attended, with

friends, a concert at the Royal

Festival Hall given by the

International Staff Band of the

Salvation Army. Awaiting the

train home to Tonbridge late at

night, Leon collapsed and died on

platform C at Waterloo East. His

head appropriately full of

stirring music, his sudden and

unexpected destination was one

not usually served by the South

Eastern railway.

In fact, his head was always full

of music. Even in repose, his

fingers were ever active on the

arm of his chair, perhaps a Bach

toccata or a brass cadenza. Who

could say? And not just every

waking moment - the music entered

his dreams as well. He would sit

up in bed and triumphantly

announce, 'I've got to letter M',

a reference to the arranger's

practice of identifying the

salient structural progressions

of a piece by rubric letters of

the alphabet.

Music dominated his life to the

virtual exclusion of all else. He

had no other hobbies except,

perhaps, the accumulation of

facts and anecdotes but even

these were for use in his regular

'Passing Notes' column in the

Baptist Church Newsletter.

With self-deprecating irony he

liked to refer to his

achievements as those of 'a

wandering minstrel', indeed his

talents were appreciated by

musical sophisticates and

unsophisticates alike. Ever a

skilled accompanist, the

congregational singing at the

Baptist Church could best be

described as 'rousing'. His

pre-service extemporisations

('busking' he called it) were

legendary. He would find out the

theme of the minister's sermon

and weave a mix of Salvation Army

choruses and favourite hymns into

a reverent muse, beautifully

timed without fail to quietly

conclude as the minister rose to

his feet. The postlude too would

often be a thrilling paean of

praise which stopped the

departing worshippers in their

pews.

Those precepts of good

workmanship which so informed his

youth, were apparent throughout

life also in his commercial work.

The youthful exuberance, perhaps

a little showing-off to his

peers, in the earlier work

exemplified by the ITMA

arrangements, gave way to a

characteristic restraint in the

mature years, almost a puritan

self-denial and economy of form.

But students and practitioners in

the art of orchestral arranging

will always remark the style of

unexpected invention and, above

all, the consummate

craftsmanship.

Copyright Malcolm Harvey Young

2006: this article first appeared

in the December 2005 and March

2006 issues of ‘Journal Into

Melody’

|