LEGENDS OF

LIGHT MUSIC

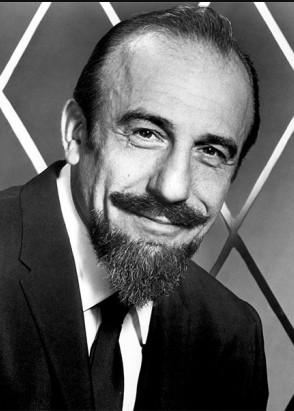

Mitch Miller

MITCH MILLER

– THE GREAT IMPRESSARIO

by PETER LUCK

For nearly 15

years from 1950, Mitch Miller was

a major figure in the recording

industry. In addition to being

one of the most dominant men in

that industry, as the head of A.

& R. (artists and repertory)

at Columbia Records in the USA,

he was also one of the most

popular recording artists at

Columbia Records, responsible for

numerous chart singles and also

hosting his own highly rated

network television show.

Mitch Miller was

born in Rochester, New York, on 4

July 1911, was interested in

music, from a very early age

began learning the piano, and at

12 he took up the oboe. He

attended the Eastman School of

Music in Rochester, where he

graduated in 1932, and joined the

music department of the Columbia

Broadcasting System network the

same year. He had several

engagements with George Gershwin

as an oboe player in the

orchestra that accompanied the

great composer on his concert

tour as a pianist, and in the

pit-band for Gershwin’s

"Porgy and Bess". He

made his reputation in

broadcasting as a solo oboist

with the CBS Symphony Orchestra

from 1936 to 1947.

When the network

acquired the American Record

Company in 1939, renaming it

Columbia Records, Miller began

appearing on records as an

oboist, and working on recordings

conducted by Andre Kostelanetz,

Percy Faith, and also with the

Budapest String Quartet.

In the late 1940s,

Miller left CBS to join the

Mercury Records label, where he

initially worked in classical

music, producing the Fine Arts

Quartet. In 1948, he became head

of A. & R. for the

‘pop’ music division,

where he signed Frankie Laine and

produced a series of major

‘hits’ for the singer,

including "Mule Train"

(a million and a half seller),

"That Lucky Old Sun,"

and "Cry of the Wild

Goose," and also conducted

the orchestra for Laine’s

hit "Jezebel." At

Mercury, Miller also signed the

singer Patti Page, who had

success with "Tennessee

Waltz", a song that had

previously been recorded by

Erskine Hawkins.

One notable period

of Miller's career found him as

concertmaster (on oboe) of the

album "Charlie Parker With

Strings". On and off from

1949 until 1953, Parker and

Miller kept close musical

company, resulting in one of the

most unusual pairings of reedmen

of all time.

In 1950, Miller

came back to CBS as the head of

A. & R. for Columbia Records

‘pop’ music division.

Columbia was among the most

successful record labels in the

United States, one of the

‘big three’ along with

RCA Victor and Decca. Among the

artists already at Columbia was

Frank Sinatra, who had been very

successful there during the

middle of the decade. However,

Miller and Sinatra never really

‘got along’

professionally, the singer

disliking the producer’s

penchant for recording light

‘pop’ and novelty tunes

which were popular with the

public.

Miller proved to

have a skilful marketing

strategy. In 1951, when Sinatra

declined to record songs he had

selected, Miller tapped a young

singer, Al Cernick, whom Miller

had signed and renamed ‘Guy

Mitchell’, and who had two

‘hits’ "My Heart

Cries For You" and "The

Roving Kind," which rode the

charts for months and sold more

than two million copies.

Doris Day was

already at Columbia when Miller

arrived as head of A. & R.

but it was while he ran the label

that she had her biggest

‘pop’ hits. In addition

to having brought Frankie Laine

to the label in the early 1950s,

he also had success with the

signing of Tony Bennett and such

new talent as Rosemary Clooney,

The Four Lads, and Johnny Ray.

Miller helped to foster the

middle/late– 1950s folk

revival when he contracted the

Easy Rider trio. They only had

one major ‘hit’,

"Marianne," in 1957,

but they wrote and recorded many

songs that became part of the

repertoires of the Kingston Trio

and the New Christy Minstrels.

It was in 1950

that Miller’s own recording

career as a ‘pop’

artist and conductor began, with

major choral recordings credited

to Mitch Miller and His Gang, and

other non-vocal numbers. Their

first ‘hit’ was a

rousing version of the Israeli

folk-song "Tzena, Tzena,

Tzena," which had also been

recorded by the folk group The

Weavers around this time. Folk

and traditional works such as the

Civil War marching song "The

Yellow Rose of Texas" proved

to form the basis of

Miller’s success when he

launched his own series of

‘Singalong’ discs. With

"The Yellow Rose of

Texas," the group was at the

Number One spot for six weeks in

1955, and continued to have other

colossal ‘hits’ with

numbers like the "Colonel

Bogey" march from "The

Bridge On the River Kwai"

(1957).

In 1958, he began

a series of Albums referred to as

"Sing Along With Mitch"

in which he led an all-male

chorus in rousing spirited

versions of mostly older tunes.

These generated numerous

‘hits’ between 1958 and

1962, and led to CBS giving

Miller a television series of his

own, "Sing Along With

Mitch." Miller had an almost

infallible ear for a

‘hit’. In 1951 he

produced 11 of the country’s

top 30 ‘hits’, had four

million-sellers, established the

careers of Tony Bennett, Rosemary

Clooney, Guy Mitchell, and later,

Johnny Mathis, saw his records

occupy the top two spots on the

charts for 14 weeks, and brought

Columbia Records from number four

to number one.

It was with the

recording of cover versions that

Miller showed his greatest

marketing acumen. In those days,

the record business was

segmented, with different records

aimed at separate groups of

buyers. Additionally, it was

customary for record companies

– even the same record

company – to issue rival

versions of singles that showed

promise, and even a difference of

a few days could determine which

version of a song became a

‘hit’. Thus, Miller got

Frankie Laine to record

"High Noon," the title

song from the Gary Cooper

western, and Laine’s version

succeeded two or three weeks

earlier than the recording by Tex

Ritter who had sung it in the

film. Initially, his recording

label, Capitol, had been

reluctant to get behind the song,

but in the event had a top five

‘hit’ with it. Tony

Bennett had a huge

‘hit’ with "Cold

Cold Heart," as indeed did

Jo Stafford with

"Jumbalaya" in the same

way.

Best-sellers like

these in the late 50s and early

60s resulted in more record sales

than Sinatra, Presley, or even

any of Miller’s own artists.

"Yellow Rose of Texas"

and "Bridge on the River

Kwai" also scored well as

individual singles. The

"Singalongs" resulted

in 23 charted albums for Miller

and Columbia, a record unmatched

in the industry, and by 1966 the

total sales of these series were

estimated at 17 million. In the

spring of 1960 "Sing Along

With Mitch" had become one

of the only recording acts of the

era to score well on television.

When Columbia had

a country ‘hit’ with

"Singin’ The

Blues," by Marty Robbins,

recorded in Nashville under the

régime of Don Law, the

label’s chief of country A.

& R. marketing drive dictated

that Miller should ask Guy

Mitchell to provide a version for

the ‘pop’ market, which

sold over a million copies. Of

course, Robbins understandably

objected to this approach by

Miller, and a subsequent one with

Mitchell’s version of

"Knee Deep In The

Blues," believing that it

could prevent his entry into the

‘pop’ market. But that

was how the record industry was

set up at the time, although this

era was drawing to a close.

As a recording

executive, Miller was perceptive

of the tastes of the times, at

least among adults. Columbia

Records was an extension of its

parent company, CBS, then known

as "The Tiffany

Network," with the widest

audience. It had the adult market

in popular music, which was the

dominant one; it had top jazz

artists, including Duke Ellington

and Dave Brubeck, and it had the

two most popular and prestigious

orchestras in the country, the

New York Philharmonic and the

Philadelphia Orchestra. Columbia

represented dignity, polish, and

depth, as embodied by the

philosophy of Goddard Lieberson.

This did not leave

much room for rock ‘n roll

music. Columbia did have a foot

in rhythm and blues through its

Epic and OKeh labels, and Don

Law, in Nashville, was able to

exploit the new music with any

signings that he chose to pursue.

But rock ‘n roll never

figured large in Columbia’s

game plan under Miller. He

personally disliked the music,

and with Columbia’s share of

the ‘pop’ music market

in the late 1950s did not take it

very seriously. At one point he

turned down Buddy Holly.

Although

Miller’s artists and his own

recordings were earning millions

of dollars for Columbia, the

Company’s market share was

slowly being eroded by changes in

public demand. Steve Sholes at

RCA, the man responsible for

signing Elvis Presley and

numerous other R. & B. stars

to that label, was catering for

teenage listeners. Label chiefs

at Decca and Capitol later had

Ricky Nelson and the Beach Boys

respectively, while Miller’s

most youth-oriented artists were

Johnny Mathis and the New Christy

Minstrels.

By the early

1960s, the decline in

Columbia’s fortunes was

already clear. Sales of albums

and adult popular music were

still healthy, but other

companies were beginning to bring

in millions of dollars and the

millions of younger listeners

that Columbia wasn’t

reaching.

Miller’s

television show remained very

popular, however, and he was

something of a superstar during

this period. But the most

important artist signed to the

label during the early 1960s was

not one of his discoveries, but a

young folk-singer and song-writer

named Bob Dylan brought into

Columbia by jazz-blues-gospel

producer John Hammond.

Hammond was

perceived as a hero, but the

company would probably not have

accepted Dylan’s presence if

Columbia hadn’t already been

selling a substantial number of

folk-style records by the Easy

Riders and the New Christy

Minstrels. Columbia was taking

rock ‘n roll a little more

seriously by 1964 with the

signing of Paul Revere and the

Raiders.

By the early

1960s, Miller (who had

successfully masterminded the

sensationally popular Little

Golden Records for children) was

able, gradually, to retire from

producing other artists and

concentrate on his

"Singalong" series.

By 1965 it was

clear that Miller’s

influence had waned. That year,

he left the Company, and

"Sing Along With Mitch"

was discontinued in 1966.

Columbia was taken over by a

younger régime under a new

president, who was determined to

take it in a new direction.

After retiring

from the TV show, he arranged a

wide range of

‘non-commercial’

projects, done strictly for the

benefit of his artistic

temperament. For instance, in

1968 he produced Here’s

Where I Belong,a Broadway musical

based on John Steinbeck’s

East of Eden. At that time he

said "I don’t mind

putting my taste on the line for

the public. I’ve found that

you cannot underestimate their

taste. They’re always ready

for something a little

better."

Miller

occasionally re-emerged as a

conductor of light classical

recordings, but otherwise largely

disappeared from the music scene.

In the late nineties, he returned

to his first love, classical

music, and began conducting

orchestras all over the world.

However, several

CDs of his best work as a

recording artist are still

currently available, and artists

he signed in the 1950s, including

Tony Bennett, Rosemary Clooney,

and Johnny Mathis, retain loyal

and even growing followings into

the new century.

© COPYRIGHT Peter

Luck, 2005

|