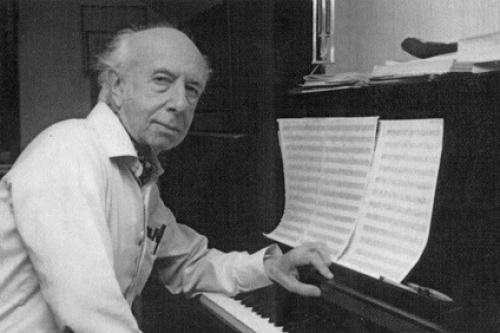

LEGENDS OF

LIGHT MUSIC

Morton Gould

MORTON GOULD, AN

AMERICAN GENIUS

By Enrique Renard

Legend has it that

Mozart could compose at age five.

That he, in fact, was too young

to write his own music, hence his

father would do the writing with

the boy standing by his side and

singing the melody.

Mozart biographers

insist that the thing goes beyond

legend, that such an unusual feat

was factual. That may well be the

case, because musical genius,

similar to that of any other

field of endeavor is a

spontaneous thing that cannot be

rationalized. It is also quite

infrequent. There have been very

few Mozarts that history could

account for. Amazingly, one of

them was born in the USA, New

York, December 10th, 1913, the

son of James Harry Gould (real

name Isidor Godfeld, of

Bulgaria), who migrated to the

USA on May 1910, and who, among

other chores oriented to economic

survival, used to play fiddle in

a Yiddish Theater.

James’

economic survival was seriously

marred by great business ideas

and horrible execution. He once

came up with an idea for an

engraved wooden compact to be

used as a cigarette or lipstick

holder. It would be manufactured

in Austria, and upon sample

showing it attracted immediate

attention, reflecting a huge

first order. The problem was that

the items were handmade, and to

fill the order would have taken

years! The deal of course fell

through and economic misery

continued to hound James, despite

which, and with the additional

burden of bad health, he managed

to marry Frances Arkin, a pretty

young woman from a German-Jewish

family he had met on the boat

from Europe and which he had

reconnected with during a visit

to recover his health at the N.Y.

Catskill Mountains.

James and his wife

settled in Queens County, then a

scarcely populated New York area

of rapid urban development, and

it was there that their first

three children were born: Morton,

December 10th, 1913, Alfred, June

23rd, 1915, and Walter, April

12th, 1917.

Music was not the

life of the family then, but it

was important to them. James

would play the violin and at the

household there was a player

piano complete with rolls of

popular classics such as Light

Cavalry Overture, Poet and

Peasant Overture,

Rachmaninov’s Prelude in C,

Chopin’s Polonaises, and

other famous classical pieces. It

is quite likely that the frequent

listening to such music awoke the

prodigy in young Morton at the

tender age of 4, for in an

interview with Roy Hemming in

1985 he said that one day his

mother Frances heard the piano

being played at the living room

(probably somewhat hesitatingly).

Puzzled, she went there to

investigate and found little

Morton playing away with his

chubby little fingers, imitating

what he had heard from the rolls.

His father James

had, however, a different version

as to the discovery of his

son’s talent. He stated that

one day upon return from work he

heard a flawed rendition of

"Stars and Stripes

Forever" being played at the

home piano. To his surprise he

saw young Morton at the keyboard.

The sound was not coming from the

roll.

Frances recalls

that the family finally seized on

the boy’s talent only after

an occasion in which James was

away on business. Morton, then

barely five and depressed by his

father’s absence, went over

to the piano and played a sad

melody of his own. "It was

at that moment", she said,

"that I realized we had

someone quite unusual in the

family".

But financial woes

seem to besiege the family

endlessly, fueled essentially by

James’ flawed attempts at

doing profitable business. He

would gain employment for a

while, but then he would quit

enthused by some business

prospect at hand which eventually

wouldn’t work. As a result

of some unpaid debts someone came

over and removed the piano from

the household. Frances was

devastated (and probably so was

Morton despite his young age).

But James was a salesman, and he

managed to hustle a piano back

into his home, thus avoiding

unnecessary interruption in his

son’s musical development.

Morton took his

first piano lessons in 1919 from

Ferdinand Greenwald, a local

piano teacher who, apparently,

didn’t attach much

importance to musical theory. He

did not teach his pupils how to

read music. But there was no

stopping to Morton’s rapidly

unfolding talent. Eventually he

took classes with a

Vienna-trained musical teacher at

the Institute of Musical Art, a

few years later.

But it was

Greenwald who was the one

involved in that famous and

factual story about Morton’s

beginnings as a composer that

parallels that of Mozart’s.

The boy was scarcely six years

old when he came up with what was

appropriately titled "Just

Six, Waltz Viennese by Morton

Gould" transcribed by

Greenwald into a score, and the

illustrious career of one of the

most talent and prolific American

classical music composers was

launched then and there. Morton

refused to feel proud about that

accomplishment, calling it

"pretty awful, nothing but a

sweet little waltz with some

schmaltz in it…"

Schmaltzy it may have been, but

try to imagine a six year old

composing a waltz, however

menial. It isn’t easy. As a

matter of fact it becomes nearly

impossible.

It may come as a

surprise to readers who have been

Morton Gould’s fans as a

composer, arranger and purveyor

of what is termed Light

Orchestral Music, to know that he

composed several symphonic

concertos, for piano, for violin,

for viola, for tuba, etc., plus

several symphonettes. He

arranged, composed and conducted

numerous Tin Pan Alley songs, and

had several LP albums masterfully

arranged that sold well. But this

was not something he was proud

of. He saw it as a necessary

commercial thing oriented to give

him financial income and

security, especially considering

that he had been appointed the

sole provider for his family.

James took upon himself to

conduct Morton’s career

along such lines, and the young

man went along with it staying

with popular music in radio shows

and records despite his strong

inclinations to compose and play

classical music that could be

termed "serious".

The extent to

which his father’s guidance

interfered with an appropriate

perception on the part of

American and European music

circles about Morton Gould’s

talent as a serious classical

musician and composer cannot be

overestimated. The impression

gathered was that because he

arranged and played Jerome Kern,

Cole Porter and Gershwin songs on

the radio he could not possibly

be a "serious"

musician.

Inevitably, he

eventually fell into that well

known mistake musicians and

critics who call themselves

"serious" invariably

fall. Light Orchestral Music,

arranged and played by a

symphonic outfit cannot be

considered "serious"

music. Oh, no. Only traditional

classical music deserves such

consideration. I submit that this

perception comes from a wrong way

of focusing the different styles

in music. There is of course what

is termed "pop" music.

But the term represents a

dangerous generalization. What is

"pop" (a contraction of

"popular") in music? Is

it country music, with its

simplicity, repetitive sound and

musical limitations? Yes, it

would fit that description. But

then, what about jazz? Is that

"serious’ music, in its

multiplicity of forms? To some,

no, it is not. Too raucous, too

syncopated. Well, what about Tin

Pan Alley or Broadway songs? No,

not exactly. Too simple, most of

it is sentimental mush, and too

brief. What about when they are

arranged for large symphonic

orchestra. Well, no. They are too

melodic, you see. And those

lyrics! Too sentimental. No.

That’s only for simple

minded people with not enough

musical sensitiveness to

appreciate Bach, Beethoven,

Charles Ives or John Cage.

Sch÷nberg and his 12 tone scale?

Oh, yes! Stravinsky and his

violent atonality? By all means!

That is indeed

"seriousness" in music.

Seriously?

It is an

undisputed fact that in music,

perhaps more than in any other

field of the arts, with the

probable exception of painting,

there is a wide variety of

tastes. What is it that

determines taste in music is

difficult to tell. Individual

sensitivity, a good ear, good

taste, a natural ability to

recognize beauty in sound

(whatever the source), cultural

upbringing, you name it. It is

also unquestionably true that

there is music that can scarcely

qualify as such. A good example

of this is a composition by John

Cage called "Four

Minutes" that constitutes

total silence. Mr. Cage comes in

while the orchestra sits there

waiting for him. He bows, then he

stands in front of the symphonic

outfit (oh, yes, it has to be

symphonic, you see) and

doesn’t move a muscle. After

four minutes - hence the title -

he bows again and leaves. The

attendees applaud politely,

looking grave and knowledgeable.

This, to them is the epitome of

"serious" music, it

would seem.

And then we have

Charles Ives, touted by many

critics as a true genius of

"serious" music, who

got furious at his publisher when

the man changed in one of

Ives’ scores a note that

seemed totally wrong and out of

place. "You are trying to

make things nice…", he

said. "Please

don’t… I want it like

that: as unmusical as

possible…"

Let’s take

another example. This time from

one of the greater exponents of

Rock-and-Roll: Ozzie Osborne,

whose presentation included

eating live chicken and bats on

stage under fiercely loud noise

from drums and the distorted

wailing of amplified guitars

being smashed against the stage

floor, with blood spilling

generously over the interpreters

while a crazed audience of mostly

teenagers howls thunderously with

pleasure.

Personal tastes

aside, I would venture to say

that the aforementioned examples

have nothing to do with music.

They have to do, in the first

instance, with the gigantic ego

of the late Mr. Cage, and his

insatiable appetite to be

considered different, therefore

special, superior to everyone

else. In the second case, two

elements concur: a) Mr.

Osborne’s appetite for

money, and b) a desire to be and

get others worked up into a

frenzy (hence the prevalence of

drugs among rock-and-rollers).

But music is nowhere to be heard.

Thus we can now

safely, I think, discard the

aforementioned examples as

"serious" music. The

problem is that, at least in the

case of rock, they are immensely

profitable despite its almost

complete lack of musical value,

if we are to consider the opinion

of reputable musicologists who

have carefully analyzed the

genre.

What has all of

this to do with Morton Gould, you

may be asking? It has everything

to do with him. By age 20 Gould

had developed into an

extraordinary musician, with a

remarkable ability to compose at

classical level as well as

lighter pieces when he wished or

when commissioned for it. By then

his father James as well as the

rest of the family got used to

the idea that their financial

woes could be solved by

Morton’s musical career and

the financial rewards it was

supposed to bring. This turned

out to be a misconception. Under

James’ direction,

Morton’s musical career

never really took off.

Commissions were

plenty, for festivals, for radio

shows, for symphonic works played

by famous orchestras, for

introduction of his own classical

compositions, for ballets, for

movies. Most of this output was

lauded by his peers and by

reputed critics. But the general

perception among the public,

producers and the musical

industry in general of Morton

being only a Cole Porter light

music man, just a "pop"

music arranger, remained with him

as a stigma he could never quite

remove from his career.

Morton was able to

appreciate tunes from Tin Pan

Alley and Broadway, composers

such as Cole Porter, Gershwin,

Jerome Kern, Irving Berlin, and

other writers of that wonderful

period covered by the 20s, the

30s and 40s, where songs were

composed which are still being

recorded and playednearly 90

years later! But these were not

considered "serious"

music by the pundits of the time.

It is a fact that Chopin,

Rachmaninov, Tchaikowsky, Liszt,

and even Beethoven, used folk

themes in their symphonic works.

The "nationalists" that

followed, such as Khachaturian,

Enescu, Falla, Albeniz, Rodrigo,

Grieg, Rimsky-Korsakov, Smetana,

Vaughn Williams and others did so

too. Should we be inclined to

consider their work "not

serious" because of it?

It seems to me

that this type of snobbery should

be recognized for what it is:

something valueless, destructive

and unfair. Unfortunately, Morton

Gould himself was not immune to

that stereotype, to the extent

that he used to deprecate his own

work. He once stated that he did

not feel "patronizing"

towards popular music when

referring to the aforementioned

popular songs. The type of music

heard on the radio and records

during the decades of the 20s,

30s, and 40s were something he

enjoyed to some extent, but that

he worked with mainly because of

its commercial value. His inner

conflict developed because of the

need to record and play what his

father told him to in order to

make money versus and his longing

to compose and play

"progressive" classical

music, atonal and otherwise. At

age 30 his compositions included

shades of jazz elements such as

the blues, folk and a tendency to

go along with Bernstein, Hanson,

Barber, Ives and other American

contemporary composers he admired

but perceived as competition.

And, for some mysterious reason,

Gould had serious doubts about

his own musical talent, even

suffering bouts of depression as

a result. He was under contact

with Columbia for quite a while,

but in 1954 he moved to RCA.

At RCA they had an

eye on Kostelanetz and his

enormous sales input with Light

Orchestral Music, reaching over

53 million by the early 50s for

Columbia, and they wanted

something similar. Gould had

radio contracts where he had been

presenting popular tunes arranged

for orchestras including large

string sections, hence RCA felt

Morton was their chance to attain

similar success. But they

encountered a problem.

Gould’s musical concept was

entirely different from that of

Kostelanetz. He once stated:

"I cannot just play the

melody straight. I state the

theme, and then go somewhere

else". That may have been

musically interesting and

correct, but it was not popular.

Percy Faith and Jackie Gleason

had undoubtedly the greatest

measure of popularity then and in

the years that followed, plus the

greatest sales numbers with Light

Music essentially because they

played the melodies absolutely

straight, something quite

uninteresting for the better

educated ears. But an educated

ear is not to be found at popular

levels. Hence the continual

battle between producers and

musicians. Musicians like Gould

wanted to record interesting

music. But that didn’t sell.

Uninteresting music played by

large orchestras did sell by the

millions, and Morton had to

comply. Still he managed to

always inject interesting

concepts in his arrangements of

popular tunes, special sonorities

and colours, sounds that made it

possible to quickly identify The

Morton Gould Orchestra, as it was

labeled.

By the mid 60s and

on, some of the surviving

arrangers from the 40s and 50s

with famous orchestras were being

asked to play rock! That was an

enormous absurdity, but the music

business is crammed with people

who don’t care about music

but care very much about money!

Gleason was a businessman who had

violent disputes with his

arrangers when they wrote some

interesting phrase in a score. He

forced them to write what people

liked. "Stick with the

melody!...", was the order,

and he sold millions of LPs world

wide. But for true musicians,

interested in good music and new,

interesting musical ideas, the

situation was sheer torment, and

the era of Light Orchestral Music

came to an end by the mid sixties

as a result.

Morton was a

complex man. The dichotomies

present in his character could be

puzzling. He was essentially a

shy man, quiet and unassuming,

who could go into a fit of rage

that sometimes terrified his

immediate family. The possessor

of a strong libido, he was what

someone would euphemistically

term "a ladies man".

Physically he wouldn’t have

conformed anything resembling

masculine beauty, far from it. He

had an unusual, long, pear shaped

face, a receding chin and too

ample a forehead. But he could

whisper into the ear of a woman

such poetic, sweet words, he

became quite successful at the

art of seduction. He was

extremely eloquent, both orally

and in writing. But, as he

himself insisted, he had only two

true loves in his life, and both

were named Shirley.

The first one was

Shirley Uzin whom he fell in love

with at Richmond Hill High School

"physically, intellectually

and in every conceivable

way", he stated. He felt she

was his twin soul, a part of him

that had been missing all his

life. She was an intelligent,

well read and cultured young

woman who appreciated good music,

"with none of those

ridiculous feminine inanities

most girls have concerning

sexuality, therefore she is

regarded as abnormal, immoral and

God knows what", he wrote to

Abby Whiteside, one of his first

teachers and a dear friend. The

marriage took place in 1936, but

it was doomed to disaster.

Shirley was an intensely

independent woman, not in the

least interested in being a

housewife or taking care of a

husband. She was politically

inclined, and she is said to have

been a member of the American

Communist Party, which eventually

caused Morton to be investigated

by the infamous U.S.

Congressional Committee for the

Investigation Un-American

Activities during the 50s, with

no consequences.

Morton was not

much of a householder either. One

morning Shirley prepared some

rice for Morton’s lunch in a

square Pyrex container, telling

him: "Just take the rice the

way it is, put it in a pan, and

light the stove. Once warm, put

it in a plate. Don’t do

anything else". When Morton

got hungry, he went into the

kitchen and followed directions

placing the dish into the pan,

lit the stove and ambled back to

work. "Suddenly there was

this horrible explosion", he

says, "and I didn’t

know what had happened. The

kitchen looked like a World War I

battlefield…" To this

day, those sitting in that

kitchen and looking at the

ceiling will be baffled by those

poke marks in it. Little would

they suspect they were caused by

rice!

On another

occasion he decided to warm up a

frozen food item and placed it in

a pot with hot water without

removing it from the box. The

reader may now gather an idea of

Morton’s culinary abilities.

Interested more in

her politics and in her

independent ways, Shirley did

nothing to save the marriage, and

Morton, still quite young, had no

way of dealing effectively with

the situation. To his dismay,

divorce became inevitable.

After a few years

and a number of affairs he said

to be meaningless, around his

30th birthday Morton started to

date vivacious and pretty Shirley

Bank, youngest child of an

affluent Jewish family from

Minneapolis. Somehow now free

from his fixation with Shirley

Uzin, Morton fell in love head

over heels with his new Shirley,

who held a degree in English and

Spanish from the University of

Minnesota and lived part of the

year in New York. They met on a

blind date in 1943, and embarked

in a peculiarly intense love

relationship. She was sweet and

innocent, and seemingly only

interested in him. They were

married on June 3rd. 1944 and had

four children.

Shirley Bank was

not interested in music at first,

but she eventually came to like

and admire her husband’s

work and offer him every support.

She was seven years younger than

him. Still, as years went by, a

feature in his character

increasingly started to annoy her

and ended driving a deep wedge

between them that ended in

divorce as well: he became

tighter and tighter with money

concerning her and the household,

and she intensely resented that.

Independent and determined, she

came to regard him as a nuisance,

and the final rupture was

inevitable after a good number of

years.

Meanwhile,

Morton’s musical career

flourished inevitably. He

composed the now famous American

Symphonettes and Concertettes,

short symphonic works where he

tried to state an American

classical musical language with

jazz and folk music overtones

masterfully blended into his

symphonic structures. Fritz

Reiner, of the Chicago Symphony,

admired his classical works and

so did Dimitri Mitropoulos,

renowned classical conductors at

the time, who continually played

his music. He gave piano

recitals, was with the New York

Philharmonic as guest conductor

on several occasions, and

conducted the Chicago Symphony

and several other Symphonic

Orchestras all over the world

featuring his own works together

with other classic repertoire.

Among his works we should

mentionAmerican Salute, American

Ballads, Classic Variations on

Colonial Themes, Spirituals for

Orchestra, Cowboy Rhapsody, Latin

American Symphonette, Minute Rag

Waltz, Stringmusic, and countless

other symphonic works. He wrote

the music for the ballets Fall

River Legend, Arms and a Girl (a

Musical) and Clarinade. His was

the music for Holocaust, the well

known TV Miniseries. He collected

7 Grammies as a result of his

enormous talent and output. In

1994 he was awarded the Kennedy

Center Honors, and in 1995 he was

awarded the Pulitzer Prize for

his composition Stringmusic.

Of his Light Music

LPs, three stand out as

extraordinary examples of light

music turned into real symphonic

pieces, all recorded in the 50s:

"Memories", featuring

songs from the 20s, wherein he

manages to get the whole

orchestra to swing, not an easy

feat. "Kern and Porter

Favorites" and "Beyond

the Blue Horizon" came later

in arrangements with a lovely

rhapsodic style. Upon careful

listening to his arrangements of

these songs for orchestra, one

concludes that it is impossible

to arrange them better. It’s

not only the technical

virtuosity, the imagination to

improvise with lovely variations

on the themes, the colours he

injected or the good taste in

sound he displayed. It is also

the emotion he conveyed without

any sort of cheap sentimentality

or mush. My friend Frank Bristow

once told me he had tears in his

eyes listening to Gould’s

arrangement of Time on my Hands.

Those songs, great as they are,

never reach your heart as deeply

as they do when arranged and

played by Morton Gould.

The 70s were a

painful period for Gould. Light

Music had practically disappeared

from radio and recordings,

commissions started to falter as

well, and the financial

arrangements concerning his

divorce from Shirley Bank left

him in a precarious financial

position. But then something

happened that saved the

situation. He was appointed

president of ASCAP the American

Society of Composers, Authors,

and Publishers, with a six figure

salary. At the time ASCAP was

said to be a veritable snake pit

besieged by internal conflicts,

with two prominent Board members

vying for power who apparently

felt that they needed a president

with no guts to continue their

maneuverings unabated. Morton,

then aged 72 and of gentle

demeanor, appeared as someone

they could easily override.

Theirs was an unfortunate

miscalculation. Behind the gentle

fašade there was a steely

determination, a penetrating

intelligence and a huge deal of

experience in the music business

now displayed by the new

president. After a while the

executive troublemakers were

removed from the organization,

now out of danger when facing the

competition from BMI that was

threatening its extinction. Gould

presided 8 years over ASCAP, the

best presidency it ever had,

while in the meantime composing

and conducting symphonic

orchestras all over. He never

stopped. "Composing is my

life", he once stated,

"If I stop, I’ll have

no life".

Morton Gould died

on February 21st, 1996, aged 82.

He had been invited to play his

music at a concert hall in Disney

World, in Orlando, Florida. Those

who knew him well observed he

seemed weaker than usual that

day, and he complained of not

feeling very well. Yet, he went

through rehearsals with the

orchestra, looking frail and

somewhat stiff, but he signed

autographs and chatted with those

present. The following morning,

his daughter Deborah noticed he

was late in rising, heArd a noise

and looked into his room. He was

on the floor, leaning against one

side of the bed. An artery had

ruptured near his heart, and he

was gone.

He was a prodigy,

indeed, an unquestionable but

never quite appreciated American

musical genius, one that only

time will reveal in his true

stature, as is often the case

with great artists.

During his final

years Morton Gould was a member

of The Robert Farnon Society.

This article

originally appeared in the

December 2009 issue of

‘Journal Into Melody’.

|