LEGENDS OF

LIGHT MUSIC

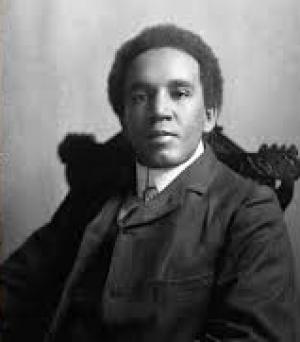

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

CENTENARY MAN : A

MEMOIR OF SAMUEL COLERIDGE-TAYLOR

(1875-1912)

By Philip L Scowcroft

As I write in

December 2012, it is still a

hundred years since the death of

Samuel Coleridge- Taylor, a

composer of talent who, although

he composed a Symphony, a Violin

Concerto, a Ballade in A Minor,

premiered at the Three Choirs

Festival having been given the

imprimatur of approval by Edward

Elgar, no less, chamber music (a

Nonet, a Clarinet Quintet and a

String Quartet), mostly dating

from his student days at the

Royal College of Music where he

studied with Stanford, and

several cantatas. Of the latter

we do not now hear Meg Blane,

Kubla Khan and A Tale of Old

Japan but for a long period

choral societies in the North of

England remained faithful to the

trilogy, The Song of Hiawatha and

during May 2013 the Doncaster

Choral Society is to revive its

most famous "third",

(actually its first third),

Hiawatha's Wedding Feast. However

his memory is primarily kept

green by performances of works

which we can regard as diverse

examples of light music, of which

more in a moment.

He was born in

London on 15 August 1875, but his

early years, at least, may be

reckoned as under-privileged. His

father, a black physician,

originally from Sierra Leone,

deserted Samuel's (white) mother

to return to Africa. Samuel's

colour was a potential

complication, though he did not

suffer from colour prejudice as

much as we might think. Both

during and after his time at the

RCM, he received words of

encouragement and particularly so

after the success of Hiawatha in

the years after 1900. By this

time he had married Jessie

Walmisley, a fellow RCM student,

and a son and a daughter,

Hiawatha and Gwendolyn Avril,

were born in 1900 and 1903. To

support his family, Samuel had to

take on more work as conductor,

teacher and adjudicator than he

would no doubt have liked. His

need for money may account partly

for the fact that so much of his

output was light music and more

readily saleable. In mid career

(1903-08) his creative urge

apparently declined. He died on 1

September 1912, aged barely 37,

of pneumonia, attributable

probably to his non-composing

activities and the overwork which

came in their wake.

Samuel's

attractive lyrical impulse and

weaknesses in form and thematic

development may also account for

his prediliction for lighter

forms over symphonic music.

Although he reckoned himself to

be English he did not eschew

negro-based music and introduced

its colour and rhythm, proudly we

may think, in works like the

rhapsody The Bamboula (1910),

which retained its popularity up

to mid century.

Samuel composed

some half dozen incidental scores

for the live theatre, most

notable being Nero(1906), whose

March was used for the 1924

Pageant of Empire, Othello (1911)

and Forest of Wild Thyme (also

1911) which yielded Three Dream

Dances, Scenes From an Imaginary

Ballet and A Christmas Overture

which has been heard in recent

weeks on Classic FM in a

recording conducted by Gavin

Sutherland. When he died he was

writing a Hiawatha ballet (not

musically connected with the

choral trilogy) which was

completed as two purely

orchestral suites, nine movements

in all, by the ever-industrious

Percy Fletcher.

Coleridge-Taylor

made the genre of the light

orchestral suite peculiarly his

own at least for a time. We must

remember that when he died Eric

Coates' Miniature Suite, his

first concert suite, was only a

year old. Samuel had penned Four

Characteristic Waltzes, which

excitingly showed the flexibility

and variety achievable with the

same basic rhythm, as did Three

Fours. Other suites like Cameos,

Contrasts St. Agnes' Eve and

Scenes From an Everyday Romance

(1900) earned success for a time,

but much the most popular, to

this day in fact, was Petite

Suite de Concert (1911),

especially the delicious

"Demande et Réponse"

which may quite often be heard in

either orchestral or piano solo

guises. Most, maybe all, of

Samuel's suites appeared in piano

versions which sold quite well

for him though not all were

orchestrated by him; Henry Geehl

did the honours for Three Fours,

Norman O'Neill for Four

Characteristic Waltzes; Moorish

Tone Pictures (1897), African

Suite (1898), Moorish Dance

(1904) and Two Oriental Valses

came before the exotic music

travels of Albert Ketèlbey. Not

all Samuel's instrumental

miniatures were for piano solo.

The violin was his own instrument

and this can be seen from the

violin/piano essays Two Romantic

Pieces (Lament and Merrymaking)

Opus 9, Valse Caprice (1898) and,

also from 1898, the Gipsy Suite

Opus 20 which was fairly recently

recorded in an orchestral

version. He even penned one or

two organ pieces.

The vocal

counterpart of light instrumental

miniatures was the drawing-room

ballad. Coleridge-Taylor's solo

songs, upwards of a hundred of

them, were mainly of the ballad

type. Not perhaps the

doleful-sounding albeit shapely,

Sorrow Songs, to words by

Christina Rossetti, revived in

Doncaster, my home town, during

2012, but to exemplify this part

of his output I would list the

titles of Eleanore, still to be

heard occasionally, Big Lady

Moon, third of the Five Fairy

Ballads of 1909, Sons of the Sea,

a favourite of the great Peter

Dawson, The Lee Shore, Love's

Passing and The Gift Rose. For

me, however, his greatest ballad

is Onaway, Awake Beloved from

Hiawatha's Wedding Feast, the

only solo in an otherwise

all-choral cantata.

Coleridge-Taylor wrote choral

miniatures as well as extended

cantatas and at least two of

these retained their popularity

with small choirs throughout the

UK for decades: O Mariners Out of

the Sunset and, set more

memorably by his teacher

Stanford, Drake's Drum. The

Bon-Bon Suite (1908) for baritone

solo chorus and orchestra is a

light concert suite with voices

added. Sentimental, apparently,

but brilliant and gossamer-like,

I would love to hear this.

Coleridge-Taylor's

lighter music long kept his name

alive and arguably still does.

One is inclined to doubt whether

he would have liked that fact any

more than did Sullivan, German

and Haydn Wood, to name but three

others. Such considerations need

not worry us, of course; we have

merely to enjoy it.

This article first

appeared in ‘Journal Into

Melody’, issue 195 April

2013.

|